Exlibris – or Nothing. Lifestyle, Advertisement, and Wanting to be Someone

Objects 3a, 3b, and 3c

Source: The Norwegian National Library via https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digitidsskrift_2022070780022_011

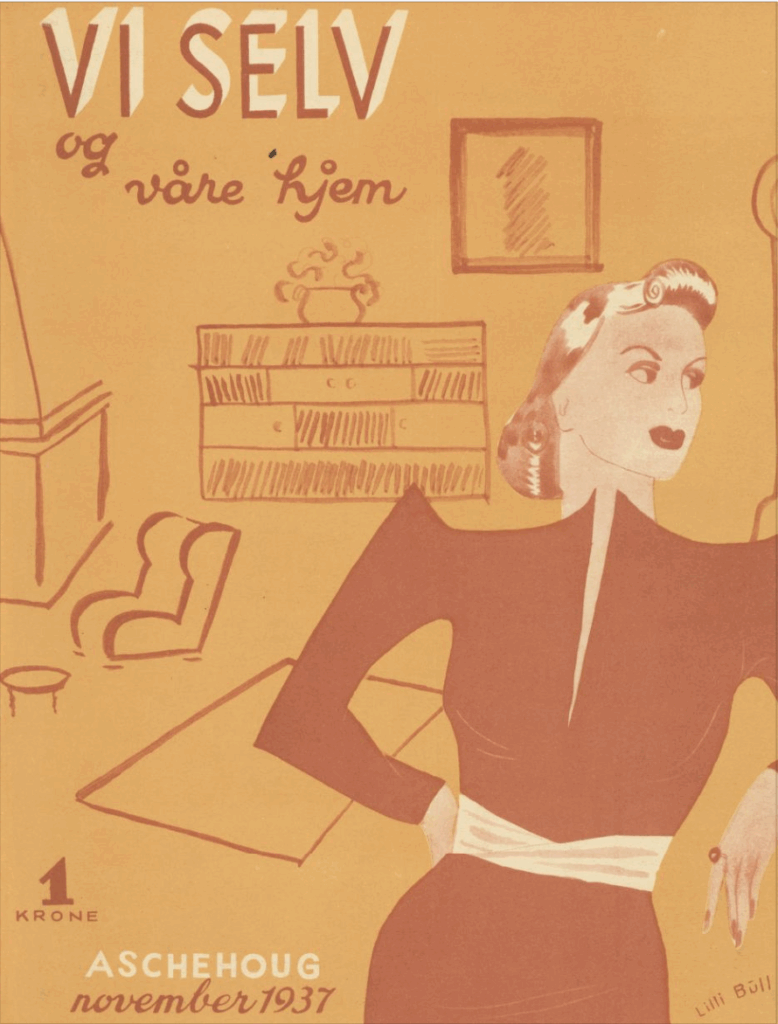

It is in the rather exclusive life-style magazine for the modern woman, Vi selv og våre hjem (1933–1955), that Hugo Høgdahl, advertisement manager at the magazine’s publishing house, Aschehoug, writes the short article “Ingenting – eller ex libris” in November 1937. Ingenting – eller ex libris, or Nothing – or exlibris in English, is placed between articles about the book(collection) as home decoration, the nobel price winning writer Sigrid Undset’s writing retreat, advice on how to start a reading circle and a few other book-related and home style related pieces. The short articles are interrupted by pages upon pags with advertisements: Stylish, modern interiors, glass- and silverware, fashion trends, topics for polite conversation, and endless possibilities for shopping anything that isn’t the bare necessities. And it is here we find the ex libris not only mentioned, but advertised for. The modern, in-style and fashionable home ought to mark their books as possessions, elegantly: “det eneste tillatelige et ex libris, pent og pyntelig anbragt på permens innerside. Til glede for eieren selv og til beskyttelse for hans bøker.”” [The only thing allowed is an exlibris, pretty and decorative on the inside of the cover. To bring joy to the owner himself and to protect his books.]

The placement of this short article frames the exlibris of pre-war Norway as a fashionable item for the upper strata of society. In the reproduced exlibris – all from Høgdahl’s own collection I suppose – modern print technology and modern artists, many of them associated with advertisment and book illustration, are represented:

- Exlibris for director Carl Janicke, by Olaf Gulbransson (1873-1958)

- Exlibris for director Bjarne Kroepelin, by Sverre Pettersen (1884-1959) fecit 1922 or 1923 – litography

- Exlibris for Inger-Helvig Paus, by Frøydis Haavardsholm (1896-1984) (draft) 1937

- Exlibris J. Throne Holst, by (advertising manager) Arnljot Løvstad (1881–?) fecit 1918, colour litography

- Exlibris Daisy Schjelderup, by (advertising artist) C. W. Rubenson (1885-1960) (silver print on blue)

- Exlibris for book illustrator and artist Albert Jærn (1893-1949). Ipse fecit. – woodcut

- Exlibris Ivar Alm by (amateur photographer) Rolf Mortensen (1899-1975) – photography

If you have the privilige of being socialised in Norway and have some interest in culture, history and society, the names of the exlibris owners above will tell you an entire story about who fancies this exclusive art form. Since I am not that familiar with Norwegian names, families and (high) society, I often don’t see the rather obvious socielty sphere these early exlibris owners inhabit. They are part of wealthy, well-established, old families in powerful positions, in work, politics and society (as I have been told by someone who knows).

So here we have it: the exlibris of the 1930s and early 1940s is a life style accessory of certain societal group. In the next posts in this series we will see that the dynamics will change throughout the 1940s. However, especially when we move on to look at the collectors of Norwegian exlibris, we will recognise some patterns.

Høgdahl’s short text can be seen as a founding document of the exlibris-mania of the 1940s and it was reprinted twice, however, notive the change in title: the word order is inverted. From “Ingenting – eller ex libris” to “Ex libris eller ingenting”. Clearly, the status of the exlibris had changed in the past 5 years since the appearance of the article. While “keep your books pristine” was the perogative of the 1930s fashionable home book collection, and if there needs to be a marker for your priced possessions, at least put an exlibris in, in the 1940s and for the intended audience of the reprints, the exlibris had become the star of the show. It was the bookplate over everything (the books themselves, even) – or nothing at all. Because if you do not partake in the exlibris fashion, you were, in fact, a nobody and your books nothing to consider.

Source: The Norwegian National Library via https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digibok_2010070206012.

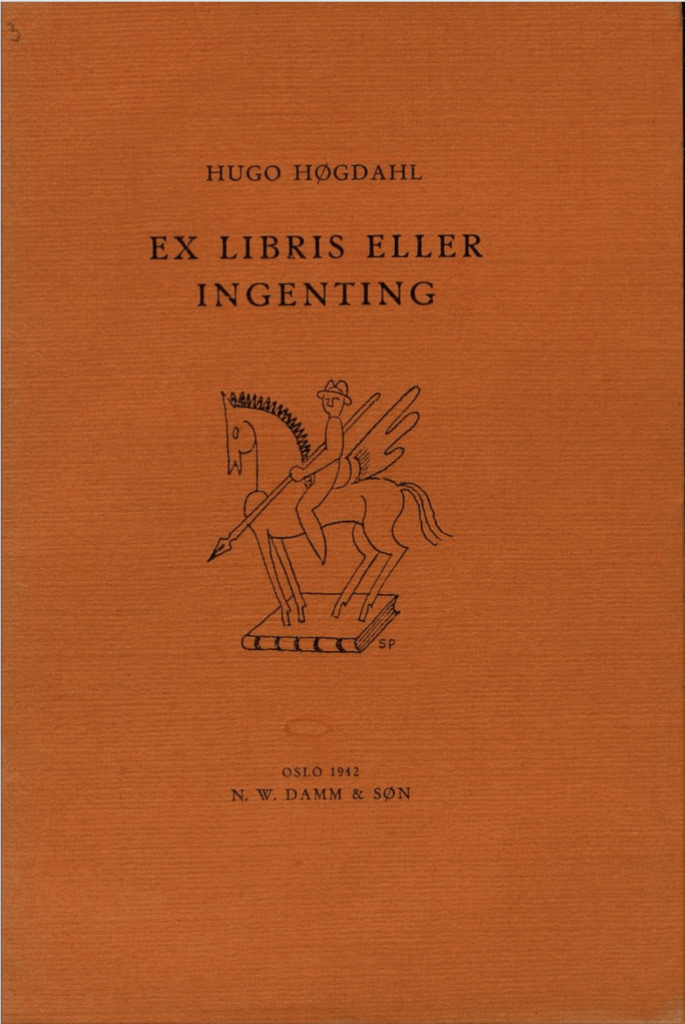

- First in 1941 [!]1 as part of the series “Småskrifter for bokvenner” in a limited edition of 400 copies, printed by N. W. Damm & Søn, manufactured in Lie & Co.s boktrykkeri. The brightly orange brochure has 21 pages and contains all the exlibris that were featured in the article. The cover and the title page have a drawing each, both by Sverre Pettersen (initals S.P.).

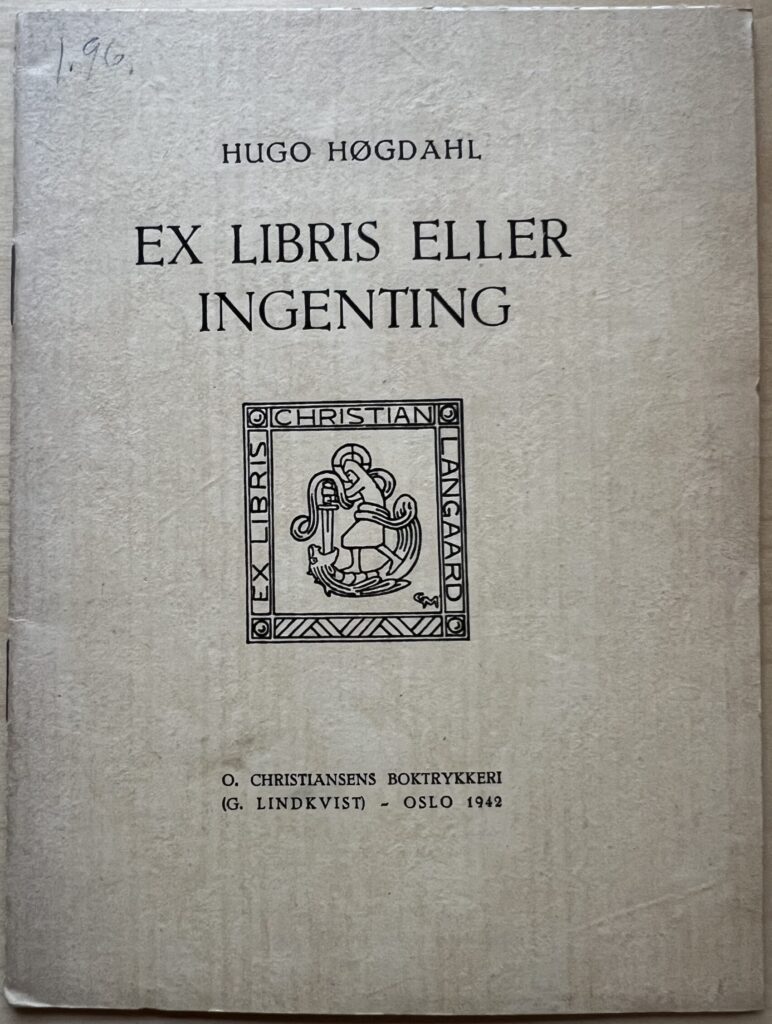

- Second in 1942, printed in O. Christensens boktrykkeri in Oslo, on behalf of G. Lindkvist. The small brochure has 16 pages, too, however, the caption for the Franz von Bayros exlibris for Poul Frost-Hansen on page 9 has been expanded. The exlibris printed on the cover of the brochure is by Gerhard Munthe for Christian Langaard.

Indeed, the 1930s saw the birth of the exlibris as a lifestyle accessory and a marker of modernity and status in the buzzing Norwegian capitol Oslo. Because soon, the winds will change and something very different will occupy the minds of the Norwegian people. On April 9th, Nazi-Germany occupied Norway and quickly changed the political and cultural landscape. Censorshop, resource shortage, Gleichschaltung of the press and publishing sector and denunziations, imprisonment and torture were on the agenda. With limited freedom and scarcity, what happened to the exlibris?

Read how the story continues in part 3 in a few days.

- It says in the 2nd reprint from 1942, printed in O. Christiansens boktrykkeri, Oslo, that Småskrifter for bokvenner was printed 1941. The edition printed by N.W. Damm & Søn, however, states clearly 1942. It could be a case of adjusting the year of publication to make it appear “younger”, a practice often employed when books were printed late in the year. It would make sense that the 2nd edition from 1942 was printed after N. W. Damm & Søn’s, but in the year 1942. Since it clearly states on the first page that it is a later edition, i tend to believe the 2nd editions printing year to be correct. Cases of making books “older” than they are, are unusual. ↩︎