What do we know and where do we start?

Book plates, or Ex Libris (or you may choose the one-word form exlibris) have been around since the advent of the printed book with moveable type in Europe. They are a book ownership mark, literally meaning “from the books of” someone. From the Early Modern Period throughout the 19th and perhaps first half of the 20th century, book lovers, graphic arts aficionados, scholars, antiquarians, philosophers, priests, erotomaniacs, and pathological collectors have had a special interest in the exlibris. And at the same time, hardly anyone knows anything about it. Few and far between are those who have seen more than the occasional book plate in an old book, even fewer those, who have taken an interest and kept the ones they came across. And perhaps rarest of them all are those, who have dedicated their lives to the collection and cataloguing of art’s distant cousin, the commissioned piece of graphic design of the size of a business card, in 50 or 100 copies. I suppose there are fewer still who make the exlibris the object of their research. I am one of those.

Some of my earliest childhood memories are me colouring in the test prints of black-and-white exlibris my grandfather made in the 1980s. The ‘knight on the hobbyhorse’ and the ‘naked lady with the fox fur’ I have in particularly vivid memory, the white parts of the prints on the pleasingly thick paper getting tinted orange, green, and red and my hand-coloured proofs littering the floor boards in the family hut in the foot hills of the Rhön. If I close my eyes, I can smell the printing ink and hear the smacking sound from the hand-cranked turning press inking up and printing copies and copies of exlibris. The press is long gone; I remember tagging along with my grandfather when he passed it on to an antiquities dealer in the late 1990s. He still drove his VW Polo Fox then, wine red. My grandfather never made another exlibris after the mid-1980s, withdrawing from the collectors’ societies and the network of international artists and collectors he had been a member of since the early 1970s. Reasons unknown. Or rather: known, but not reasonable.

But I had already been made an adept, effortlessly, by exposure. I have two children’s exlibris in my name: both exist in one copy only, they were a gift from one book plate artist and collector (Willi Richter) to another (Hubert Rockenberger). They were, in a way, not really meant ‘for me’, I was just the occasion. I had them in photo frames in my bedroom in my family’s house for years until I moved out and put them away in a box. Many years later, I was re-introduced to the world of exlibris and their collectors in 2007, I believe, when the head of the division for single sheet prints at the Berlin State Library, where I was doing an internship at the time, invited me to the annual Berlin Exlibris Meeting in the neighbourhood social centre “Rudi” in Berlin Ostkreuz. One chilly November evening, I made my way there, shyly entering the brightly lit main room where a small exhibition was set up and a couple of elderly people sat around tables fixated on binders with their exlibris, chattering, engaged in trade and exchange. I was soon discovered by the divison head, who announced me – loudly – across the room; silence and a gasp when they heard my last name. I was recognised, but not as Annika. It was the last name, Rockenberger, and with it my relation to the artist, notoriously. Suffice to say I was much the object of attention again that evening and many people introduced themselves as old friends and acquaintances of my grandfather from more than 30 years ago.

That evening, I met the great exlibris zealot Klaus Rödel and the director of the Frederikshavn Art Museum, Helge Larsen and they gifted me dozens of exlibris from their vast collections, so I might start my own with something to trade with. I also got another Willi Richter exlibris from his late wife, Ute Wermer and a selection of fox themed exlibris from Brigitte Lizinski. It might have been that same night I met Sofya Vorontsova, the young Russian exlibris artist with her especially expressive multi-coloured, organic relief prints. I remember, I attended maybe two or three meetings the following years, but couldn’t really keep the interest alive with everything else that was going on during that time. I never managed to build a collection of my own; and after speaking to grandfather who promised me to leave me his collection after his death, I got in some sort of executive paralysis where I felt I couldn’t decide on what to collect. I have always had – and still have – a strong aesthetic preference for simple woodcut and linocut prints. And the rough, strict and reduced style of Socialist Realism of the late 1960s to 1980s resonates with me. But I didn’t want it enough. I felt insecure about my choices and unoriginal, copying yet another interest my grandfather had had – and was so much better and more knowledgeable and talented in. And had abandoned. So why enter? Why even start?

When I moved to Oslo in 2012, I left the carton box with my exlibris behind. I hadn’t pulled up all stakes yet in Berlin, but I certainly didn’t have space or much of an interest in bringing them along. I had joined the German Exlibris Society, though, and received their yearbook. I didn’t read it. I considered leaving the society several times but stayed, mostly out of shame. After a difficult time which had nothing to do with book plates (and at the same time: they symbolised everything), I brought them with me to Norway in the late 2010s: in a turquoise folder, barely protected from dust and impact. But I was still removed from the exlibris world. I had tried to find out if Norway had a similar society to the German, but could not find anything. The people I talked to about exlibris did not know or understand what they were and why anyone would be interested in that. There was also a lack of antiquarian bookshops (at least: compared to Berlin. But what doesn’t stink compared to Berlin!) and galleries for graphic art.

Then it took until 2024 before I would re-enter the world of exlibris for real. The occasional browsing of Finn.no, the second-hand online marketplace in Norway, made me aware of a collection of “Norwegian Exlibris” that was up for sale. A price was not set. I initiated contact and eventually met with Petter Heier who had half of the exlibris collection of his late father, Rolf Nysted Heier. I didn’t know anything about the Norwegian exlibris in particular, nor had I heard anything about Nysted Heier, but the sheer size of the collection, some 2.500+ exlibris and several dozen books and pamphlets about the matter, were hard to withstand. We agreed on a price and I paid and we drove everything with his car to my office, knowing that I would not have any space at home. And that was it, I had gotten myself a collection and was thrilled – and felt sick to my stomach at the same time. What had I done? Why did I pay all that money for a collection that was only “half” anyways, and contained all kinds of exlibris, regardless of artistic quality and craftsmanship, their sole common denominaator was just that they were ‘Norwegian’. After the first shock had settled and I could think again, something else than my collector’s enthusiasm woke up: my research interest was piqued. While trying to get to know my newly acquired collection, I found out that there is nothing (as in zero, zilch, nada) written about the exlibris in Norway, and especially about the Norwegian exlibris. No one knows. No one cares.

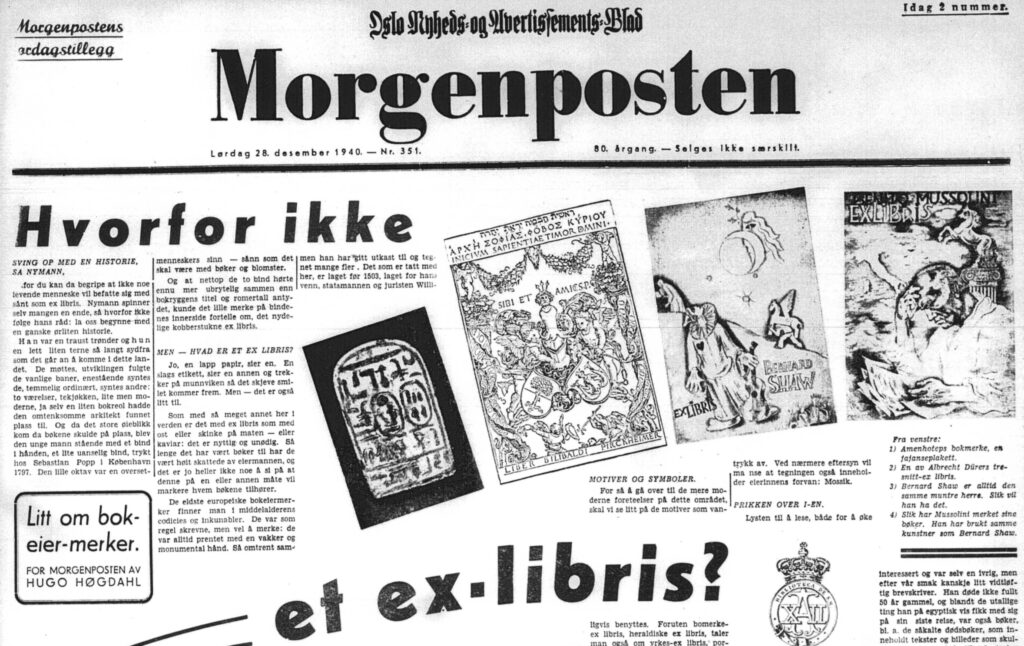

That in and of itself is not shocking. As I said before, book plates are a niche interest and research on a niche interest is even more niche. I wouldn’t have expected much. What is striking, though, is that there are thousands of Norwegian exlibris that were created in a short period of maybe 15 years, from the early 1940s to the mid-1950s, with a peak in the years of the Nazi occupation of Norway 1940-1945. The years after the occupation saw the official foundation of a Norwegian exlibris society and network activities of its members with exhibitions, special publications and pan-Scandinavian exlibris meetings in Helsinki, Gothenburg and Oslo. And then, in the late 1950s, early 1960s, it was over almost as rapidly as it had started. The exlibris disappeared again from the Norwegian stage and once more became the arcane practice of a small, intellectual elite. The great collectors of the 1940s and 1950s became inactive after trying and failing to attach themselves to international book plate societies. We don’t know what happened to their collections, but we may very well assume they share the fate of Nysted Heier’s: being passed on to the children, who don’t have the interest (or the space) and in the absence of a market for exlibris, the collections become unsellable and will get thrown away, dispersed, forgotten, neglected and decompose as time goes by.

Nysted Heier’s collection only survived partly. Both his sons inherited each half of the collection. One kept it, the other tossed it. We don’t know what was in the other half, but we may reconstruct it to some degree. There are no other collections publicly known apart from the large collection of exlibris at the Bergen Public Library, which is partly accessible with images and short descriptions online, but the majority sits in a box in the basement depot.

So, what am I doing with all of this? I have started a research project on the phenomenon of the Norwegian Exlibris, where I will reconstruct the Nysted Heier collection as a representative, contemporary layman’s collection and I will supply what he and his peers knew about the book plates, their owners, artists, printers, distributors, and the network of collectors and enthusiasts of the first half of the 20th century. In addition, I will update and complete the bibliography of exlibris literature in and about Norway and transform the 1974 catalogue of more than 8.500 Norwegian book plates into a searchable database. I believe I can write a book on the cultural history of the Norwegian Exlibris based on the materials I can gather and identify and that it will shed some light on a rather peculiar aspect of every day life during the Nazi occupation. During that moment, Norway briefly becomes a hotspot of activity at a time where everywhere else in the world the exlibris production and collectors’ activities lay in abeyance.

I am not a trained anthropologist, but I really like the method of auto-ethnography, which I will employ while I prepare for and conduct this research project. I have put a simple website online where I will occasionally post about what I do with the collection and how I go about researching and reconstructing the Norwegian Exlibris. The website can be found on https://norsk-exlibris.no/ and is written in English, my language of choice, and coded in the plainest of plain HTML. I will write a number of compact biographies of the most productive exlibris artists as well as the “Oslo Club” of the Norwegian Exlibris Society. However, artists, owners, and collectors were almost exclusively men. Therefore, I aim to dedicate a large part of the project to the female book plate owners and artists, as well as collectors, namely the Bergen based librarian and exlibris pioneer Hanna Wiig. I also plan on looking into the production process of the book plates during the Occupation period with its restrictions, censorship and rationing of resources and the exlibris’ socio-cultural function, hoping to be able to explain why there was such an incredible rise in popularity of an art form that was previously limited to exclusive circles and why it disappeared almost completely shortly after the war and the difficult post-war years were over and Norway headed toward an era of prosperity and social mobility.

And I will, though it can hardly be defended as scientific, use my engagement with the exlibris to process difficult periods in my life and the impact they had on finding out who I am and what I want. Can I be myself and make a mark on the world of exlibris when I collect, create and research them, or will I always be a lesser, unoriginal version of the notorious Rockenberger.

One Comment

Comments are closed.